Localization 2.0: Where a Brand Thrives, Not Where It’s Born

When roots lose their charm, brands turn to belonging as their new currency.

There was a time when the power of brands came from their roots. Coca-Cola, as a symbol of America, and McDonald’s, as shorthand for the “American dream,” carried global appeal. But that appeal has given way to different concerns.

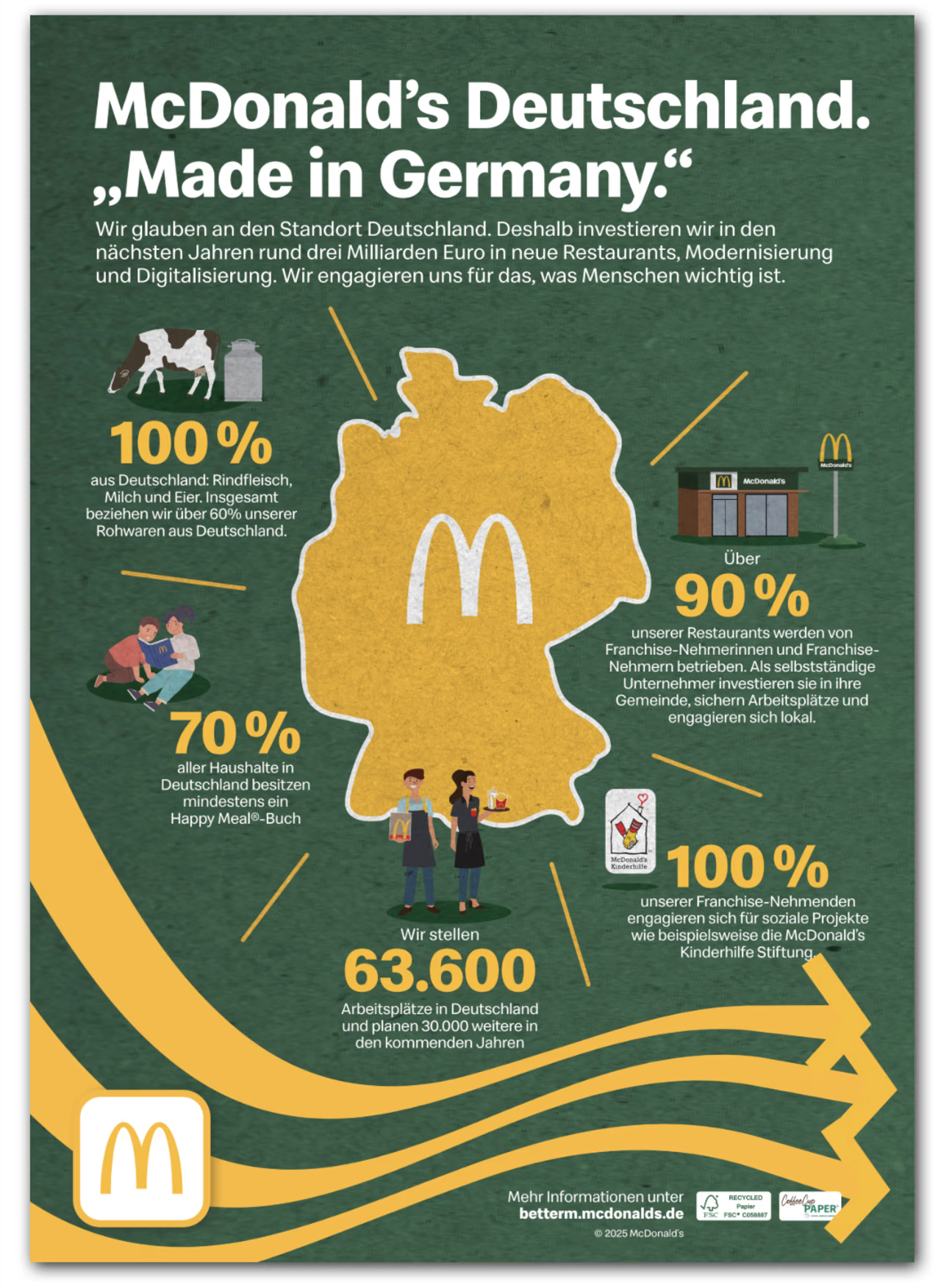

Today, the same brands are in Germany declaring “Made in Germany,” and in the UK saying “We’ve been here 125 years.” McDonald’s highlights that 100% of the beef, milk, and eggs it uses are locally sourced. It’s no longer just about taste or quality—it’s about carrying the image of a nation. At least that’s the perception. Studies suggest consumers now look not only at price and quality but also at the “passport” of a brand. Is that really the case?

Erosion in national reputations, trade wars, and political risks are pushing global brands toward new strategies. They are compelled to hide their origins deliberately. We might call this Localization 2.0. Which raises the question: is this a lasting identity or just a temporary line of defense?

Why Localization 2.0?

The first wave of localization was about product adaptation. Add a McTurco to the menu or feature a local celebrity in an ad, and it was enough. Localization 2.0, however, is about pushing a brand’s origin into the shadows, making it deliberately invisible. Coca-Cola, for instance, brings the stories of its German factory workers to the forefront. In the UK, it films commercials featuring local corner shops. The message is: “We are actually one of you,” expressed through production, employment, and cultural ties.

This isn’t just McDonald’s or Coca-Cola. As Lara O’Reilly notes, agencies are now requesting creative work that looks “less American,” with local shoots and a strong emphasis on local sourcing. Tariffs, boycotts, and regional perception risks are reshaping both the visual language and the production process.

The story in Turkey is no different. Fanta embraced the colloquial phrase “Sarı Kola” (“Yellow Cola”), embedding it directly into its campaign slogan: “If you’re a Yellow Cola fan, you’re a Fanta fan.” It’s a clear attempt to adopt consumer language rather than cling to official identity.

Burger King went a step further. In one campaign, it spelled its name “Börgır” to mirror local pronunciation. By bending even its logo to fit everyday speech, Burger King pushed its American roots to the background and reinforced the perception of being “one of us.” These are the kinds of methods big brands are now using to reduce risk.

The Consumer’s New Priority: Trust

Global events are reshaping consumer priorities, pushing price further down the list—especially in Europe. McKinsey data confirms this: 47% of consumers say supporting local brands is a primary shopping criterion. This explains why McDonald’s emphasizes that its German menus use 100% local ingredients, or why Coca-Cola highlights factory workers in its ads.

The message is straightforward: “The factory is in your country; you are the ones producing these goods.” Such rhetoric creates a zone of trust, insulating brands from political risk. Campaigns and research alike show that brands are competing not just for market share but for belonging.

The smile of a Coca-Cola factory worker in an ad, or Burger King writing its name as “Börgır,” are both attempts at trust-building—giving consumers something they can recognize as their own.

Do Surveys Match Real Life?

Take another McKinsey data point: in 2025, 42% of European consumers reported negative perceptions of American brands. On paper, it looks like anti-American sentiment should spell disaster. But does it?

Yes, boycotts and negative attitudes exist. But widespread rejection? Not really. Coca-Cola, Levi’s, and McDonald’s remain firmly in consumers’ routines. The only brand seriously affected is Tesla—largely because of Elon Musk’s personal behavior, which triggered a significant backlash in Europe.

Surveys reflect political stances, but in practice, convenience, safety, and habit often outweigh ideology. Intent does not always translate into action. Consumers may think politically, but when it comes to shopping, pragmatism wins. That’s why brands, aware of these risks, are doubling down on localization: to provide reassurance to consumers who protest with words but still make purchases out of habit.

If a product is accessible, reasonably priced, and delivers on taste or quality, political concerns fade into the background. Local storytelling alone won’t suffice. At the shelf, at the checkout counter, consumers want the brand to say: “We’re right here.” Intentions may shift, but behavior changes only through touchpoints.

Identity and Belonging

Localization, especially in times of heightened political risk, acts as a shield, reducing the fragility of consumer relationships. Yet it also creates a paradox: the very thing that makes these brands valuable is their origin. Coca-Cola, as the archetypal American drink, or McDonald’s as the emblem of fast-food culture, is part of that DNA.

Does localization strip away a brand’s true identity? I would argue, no. What we see today is primarily a temporary line of defense. Big brands will continue to build local belonging without losing their global vision. That vision remains a unifying symbol. Coca-Cola’s promise of the same taste everywhere is proof enough. Local narratives may build upon them, but the global vision remains the foundation.